In the early hours of a January morning in 1995, the sea seen from the deck was still shrouded in darkness.

Aboard a Cape-sized (large iron ore carrier) vessel departing from the Nippon Steel Corporation’s Kimitsu Works (Chiba Prefecture).

To the maritime industry journalist on board for coverage, the blast furnace of the Kimitsu Works appeared like a pre-modern object glowing before the bioluminescence of the sea.

“Iron is the nation.”

In the 1990s, steel manufacturers were the largest shippers, their influence resonating throughout the shipping industry.

“The blast furnace is the symbol of a steel manufacturer.”

The captain, who had transported iron ore from Western Australia, spoke with unwavering conviction as he gazed at the smoke billowing from the blast furnace.

■Prime Minister Suga’s Carbon Neutral Declaration**

“Iron will never disappear. From the moment we wake up until we head to work or school, we rely on iron for trains, buses, and cars – without it, we wouldn’t get anywhere.”

Steel industry insiders speak uniformly with pride about “iron.” There is no doubt that throughout all eras – from wars and upheavals to the industrial revolution – iron has driven the world forward.

Iron is here to stay.

While this fact remains unchanged, the methods of steel production are now poised for a significant transformation.

Environmental issues, which were mere catchphrases until the early 2000s, have since the 2020s become a major force driving corporate change.

On October 26, 2020, then Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga declared in his policy speech that Japan aims to become carbon neutral (CN) by 2050.

This declaration has triggered a demand across all industries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly CO2.

The maritime industry is no exception.

It is estimated that the annual CO2 emissions from global shipping are equivalent to those of an entire country like Germany.

In the shipping industry, efforts are underway to introduce LNG (liquefied natural gas) fuel, and research into various ship fuels like green methanol and ammonia is being conducted with the aim of achieving CN by 2050. However, the definitive solution is still being sought.

■Steel Industry’s Swift Shift to Decarbonization

In contrast, the steel industry has demonstrated much quicker management decisions towards decarbonization than the maritime industry.

One of these decisions is the abolition of the blast furnace, the “symbol” of steel manufacturers, and the transition to electric arc furnaces.

Steel manufacturers have outlined several roadmaps to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

These include production methods using DRI (Direct Reduced Iron) and HBI (Hot Briquetted Iron), which is compressed DRI, as well as the introduction of 100% hydrogen-reduced iron.

Among these, the most effective measure at present is the shift from blast furnaces to electric arc furnaces.

In blast furnaces, coke is used as a reducing agent to extract sufficient iron content from iron ore. During this process, the oxygen in the iron oxide combines with carbon to produce CO2. Approximately 2 tons of CO2 are generated in the process of producing 1 ton of iron.

As of 2020, the industrial sector accounted for 34% of Japan’s total CO2 emissions, with the steel industry estimated to contribute about 40% of this amount.

For a long time, blast furnaces remained the mainstay of steel manufacturers because they could produce high-grade steel that electric arc furnaces could not, such as steel used in automobiles.

Electric arc furnaces can reduce CO2 emissions to a quarter of those produced by blast furnaces. The raw materials are “iron scrap,” which comes from construction sites, automobiles, household appliances, and other waste.

There has been a perception that iron scrap collected from the market contains impurities (trap elements), resulting in a quality inferior to that of blast furnace steel. Thus, the equation has been: blast furnace = high-grade steel, electric arc furnace = general-purpose steel.

■ Nippon Steel and JFE’s Ambitious Plans

Nippon Steel, under its “Carbon Neutral Vision 2050,” has set its sights on producing high-grade steel using large-scale electric furnaces. The company is already taking significant steps towards this goal, including the construction of a new electric furnace at the Setouchi Works (Hirohata Area) and the conversion of a blast furnace to a large electric furnace at the Kyushu Works (Yawata Area) by 2030.

Similarly, JFE Steel is considering the introduction of electric furnaces at its West Japan Works (Kurashiki Area). Among the three blast furnaces currently in operation, JFE plans to halt one during its scheduled refurbishment and replace it with an electric furnace.

This shift from blast furnaces to electric furnaces by major steel manufacturers is set to dramatically change the structure of Japan’s crude steel production.

■Greenspan’s Prophecy

Former Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, once remarked, “The price of scrap iron is a leading indicator of economic conditions.” Indeed, scrap iron prices reached historic highs, around 70,000 yen per ton, just before the Lehman Brothers collapse in July 2008, only to plummet to 40,000 yen per ton by August of the same year.

According to The Japan ferrous raw materials association, Japan produced approximately 34.8 million tons of scrap iron in 2020. Despite being one of the few domestic resources for a country lacking in natural resources, Japan exported 9.37 million tons that year, resulting in a net export of 9.33 million tons.

The valuation of this scrap iron may see a significant shift in the future. The transition plans of blast furnace manufacturers to electric furnaces mark just the beginning.

The crucial question is how to effectively recycle the various types of “iron” available.

――Japan, the world’s third-largest ship-owning nation after Greece and China, considers ship scrap a valuable domestic resource and a key material for electric furnaces. This report delves into the current state and future prospects of ship scrap recycling.

(Hiruofumi Yamamoto writes this series)

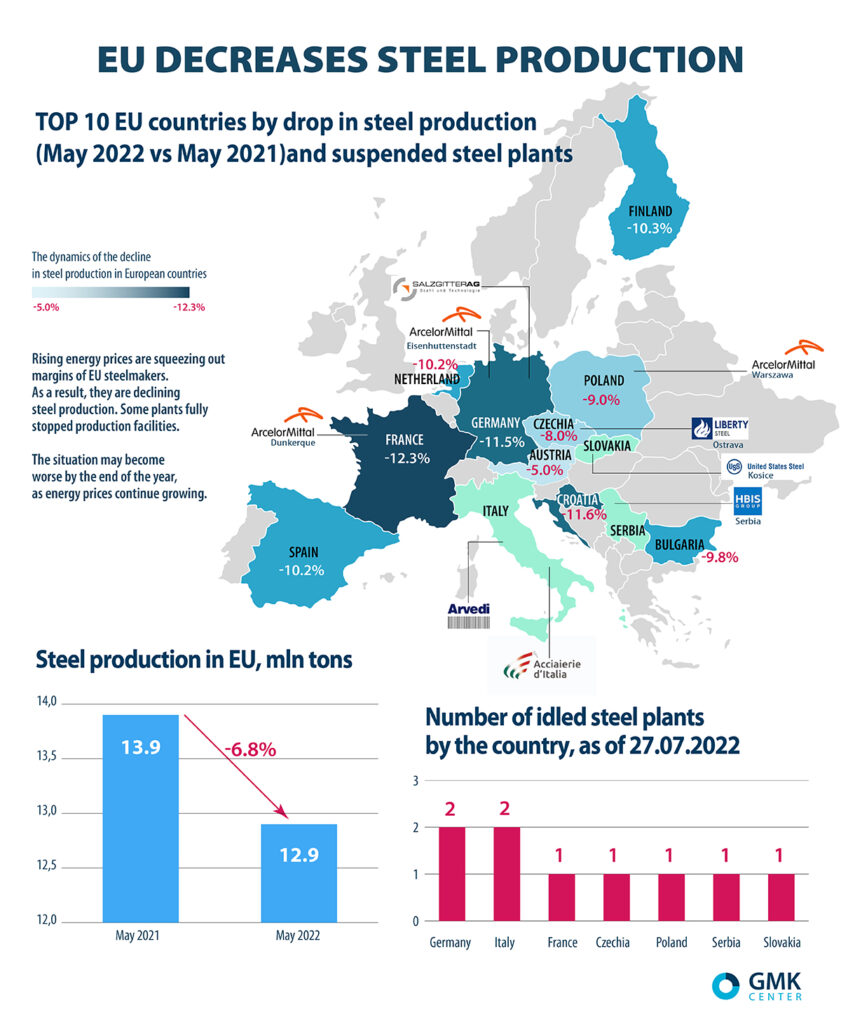

Photo courtesy =Nippon Steel, JFE Steel and GMK center

タイトル【船舶スクラップが日本を救う】

(連載、第1回)電炉シフト、温暖化防止の鍵

1995年1月早朝、甲板上から見る海はまだ暗闇に包まれていた。

新日本製鉄(現日本製鉄)君津製鉄所(千葉県)を出港するケープサイズ(大型鉄鋼原料船)の船内。

乗船取材中の海事専門紙記者の目に君津製鉄所の高炉は夜光虫が光を放つ前近代的なオブジェのように映った。

鉄は国家なり―。

90年代当時、海運業界でも鉄鋼メーカーは最大荷主としてその威光をとどろかせていた。

「高炉こそ鉄鋼メーカーのシンボルだ」

西豪州から鉄鉱石を輸送してきた船長は、高炉から吐き出される煙を眺めつつ、記者にみじんの疑いもなくそう語った。

■菅首相(Prime Ministar Mr.Suga)のカーボン・ニュートラル宣言

「鉄は絶対になくならない。朝起きてから会社や学校に行くまで、電車やバス、車など鉄がなければどこにも行けない」

鉄鋼業界の関係者は一様に「鉄」に対する誇りを語る。戦争、動乱、全ての時代に軍需から産業革命まで鉄が世の中をけん引してきたことに疑いはない。

鉄はなくなることはない。

その事実に変わりはなくても、今、鉄鋼の製造方法が大きく変わろうとしている。

2000年代前半までキャッチフレーズに過ぎなかった環境問題が、企業活動に大きな変革を迫る要因となってきたのは20年代に入ってからである。

2020年10月26日、菅義偉首相(当時)は所信表明演説で日本が2050年までにカーボンニュートラル(CN)を目指すことを宣言した。

https://www.jmd.co.jp/article.php?no=296104